Rituals for a reason

| 10. Oktober 2018

The Limbu rituals are more important than ever. Anthropologist Mélanie Vandenhelsken explores the Nepal-Sikkim borderlands to study the re-composition of an old religious practice. (© Mélanie Vandenhelsken)

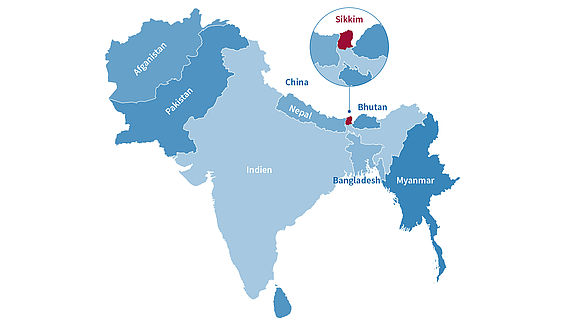

Pregnancy, birth or death: The Limbus in the Nepal-Sikkim borderlands have rituals for every stage of life. Many of them disappeared over time, but some have been preserved, and others revitalised recently. Mélanie Vandenhelsken, anthropologist at the University of Vienna, studies these changes.

Collecting ripe vegetables at every door – Sissek Patumyen is an ancient ritual celebrating the harvest. This ritual was almost forgotten by the Limbus. Very recently, the indigenous community revitalised this village ritual in order to foster a "Limbu identity". Anthropologist Mélanie Vandenhelsken, who is a member of the University of Vienna's research centre CIRDIS since 2016, studies today's cultural practices in the Nepal-Sikkim borderlands. Her hypothesis: "Politics are now an important factor in ritual dynamics among the Limbus."

To celebrate the beginning of the harvest season after a long period of starvation, the Limbus in a West Sikkim village perform the Sissek Patumyen ritual. Members of the community go from house to house to collect ripe vegetables. (© Mélanie Vandenhelsken)

Between shifting borders

When Nepal was founded in the 18th century, the Limbu's territory was divided between the Kingdom of Sikkim (today an Indian state in the northeast) and Nepal. Consequently, the rituals started to change. "Over time, Buddhist traditions in Sikkim and Hinduism in Nepal came to influence the Limbus' ritual practices and introduced differences between rituals in both places", Vandenhelsken explains.

200 years ago, British colonialists started exercising power in the Kingdom of Sikkim. To raise tax income they opened Sikkim to Nepalese migrants. The population of the region changed, and in a short time, Nepalese migrants accounted for more than 80 per cent of Sikkim's population. "For the need of the census, Sikkimese inhabitants were categorised into three ethnic groups: Bhutia, Lepcha and Nepalese. The latter category also included the Limbus who thus all ended up being registered as foreigners, whether they had always been in Sikkim or had immigrated from what had recently become Nepal a few decades ago", says Vandenhelsken.

Mélanie Vandenhelsken focuses on the role of the international Indo-Nepalese border on present-day’s re-composition of religious ideas and practices amongst Limbus men and women. (© University of Vienna)

A difference that matters

The formerly bureaucratic category became a political matter when the Kingdom of Sikkim was annexed by India and transformed into a federal state in 1975. Since then, the struggle of the Limbus has been to assert their indigeneity. "India's government dispenses state benefits based on ethnicity. Until today, the Limbus have to prove that they are not Nepalese, but autochthonous to the region in order to get access to education or employment and have a say in political decisions", explains Vandenhelsken.

Culture as resource

In this context, culture became a resource, "For political reasons, the Limbus in India have to clearly distinguish themselves from Nepali culture and religion, and this also affects their rituals. They remove all traces of Hinduism in their practice and revitalise ancient Limbu rituals."

The interaction with the people is good. "Since cultural distinctiveness is valued today for various reasons, including political ones, people have no restrictions to discuss their practices with anthropologists", explains Mélanie Vandenhelsken. In the picture: Vandenhelsken (right) and the Limbu priests Sanchaman Limbu. (© Mélanie Vandenhelsken)

In order to get an insight into ritual dynamics, Vandenhelsken studies old Tibetan and Nepali documents in the British Library and in both Nepalese and Sikkimese Archives. In addition, she carries out fieldwork in the Himalayas on a regular basis, "I am interested in the history, the literature – I collect books, look at catalogues and investigate the process of writing down the orally transmitted myths – and the actual rituals." This research aspect considerably benefits from Martin Gaenszle's contribution to the project, His research at the Department of South Asian, Tibetan and Buddhist Studies at the University of Vienna has been focusing on this process in the Rai communities in Nepal for a long time.

Rolling cameras

Equipped with cameras and audio recorders, Vandenhelsken documents the rituals, which can last up to three days. "Sometimes 2,000 people join; the community comes together and makes offerings. Priests recite Limbu mythological narratives and lead the spiritual journey", reports the anthropologist. After the ceremony, Vandenhelsken shows the video to the religious leader and they analyse the ritual together.

With the support of her co-researcher Martin Gaenszle – who now continues the research on the Limbu on the Nepali side – she will compare Nepal and Sikkim, "We are looking at connections and disconnections between Nepal and Sikkim, we study how the border is depicted in the rituals, and also how mobility of people across the border influences the reformulation of rituals both in Nepal and Sikkim."

20 years of University of Vienna Campus

Several thousand people gather at the Campus of the University of Vienna every day to conduct research, teach and study. The Campus was officially opened in 1998 on the grounds of the former General Hospital. It covers an area of 96,000 square metres. (© University of Vienna)

Open access to holy ceremonies

Videos, photos and audio recordings from Vandenhelsken's field trips will be stored and published according to open access standards in the Himalaya Archive Vienna hosted by the University of Vienna. The interdisciplinary network CIRDIS and the Himalaya Archive make the University of Vienna a great place to conduct research on Sikkim, Vandenhelsken emphasises. Before coming to Austria, she studied and worked in many different places – among others at the Nanterre University in France – but Sikkim always remained her "second home". (hm)

The project "Trans-Border Religion: Re-composing Limbu rituals in the Nepal–Sikkim borderlands" runs from November 2016 to October 2020 and is led by Dr. Mélanie Vandenhelsken at the Center for Interdisciplinary Research and Documentation of Inner and South Asian Cultural History (CIRDIS) of the University of Vienna with the support of Martin Gaenszle, Department of South Asian, Tibetan and Buddhist Studies at the University of Vienna. It is funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).