Ancient DNA shines light on Caribbean prehistory

23. Dezember 2020Large genome study brings new answers

An international team of scientists reveals the genetic makeup of the people who lived in the Caribbean between about 400 and 3,100 years ago—at once settling several archaeologic and anthropologic debates, illuminating present-day ancestries and reaching startling conclusions about Indigenous population sizes when Caribbean cultures were devastated by European colonialism beginning in the 1490s.

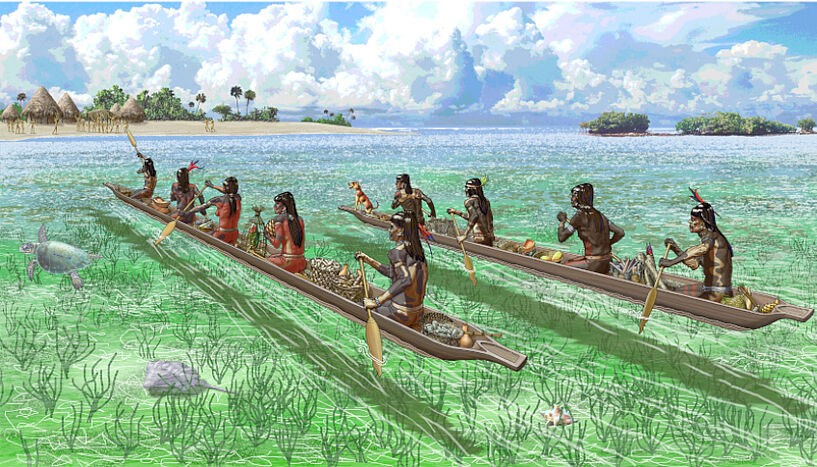

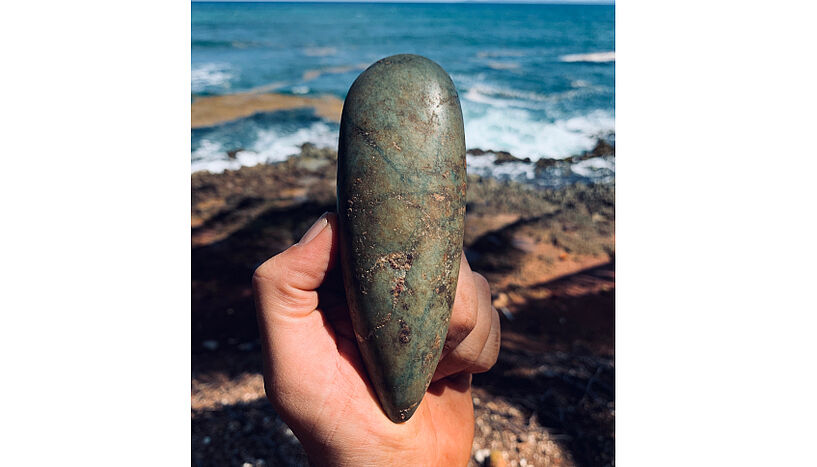

About 6,000 years ago, at the start of the Archaic Age, humans first settled in the islands of the Caribbean. These individuals lived in what is now the Bahamas, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Puerto Rico, Guadeloupe, St. Lucia, Curaçao and Venezuela. Three to four thousand years later, stone tools gave way to clay pottery and the Ceramic Age began. Another two millennia passed before Europeans sailed across the Atlantic and made first contact.

Where did these stone tool-using and clay-crafting populations come from? Were they related to each other? How many people lived in the Caribbean when the Spanish first arrived? How much, if any, ancestry can today's Caribbean populations trace back to these precontact Indigenous groups?

New answers have emerged from this largest genome-wide study to date of ancient human DNA in the Americas. An international team of geneticists, archaeologists, anthropologists, physicists and museum curators, including Caribbean-based co-authors and in consultation with Caribbean people of Indigenous descent, analyzed the genomes of 174 new and 89 previously sequenced ancient people.

"We tried to look not only into the origins of the people living in the Caribbean before European contact, but also deeply into their local networks of interaction," said co-first author Daniel Fernandes, a post-doctoral researcher at the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology at the University of Vienna.

Stone and clay

The researchers found that Archaic Age Caribbean populations are consistent with descending from a single source population in Central or South America. In contrast to previous research findings, the team concluded that these Archaic peoples likely did not have any notable ancestry from North America.

The Ceramic Age people had a different genetic profile, most similar to Arawak-speaking groups in northeast South America, the team learned. The finding is in line with archaeologic and linguistic evidence.

The ceramicists appear to have migrated to the Caribbean from South America, most likely island-hopping through the Lesser Antilles, at least 1,700 years ago, almost entirely replacing the resident stone tool-using people, the researchers found. Only a small numberof Archaic populations remained, persisting in western Cuba until around the time of European arrival.

Pots, not people

The team’s genetic and archaeological findings indicate that the potters’ genetics remained largely the same across the Caribbean century after century, and that Ceramic Age innovation arose from networks of people sharing ideas from island to island, rather than the influence of waves of new people migrating from the mainland. "Our results support connectivity networks between ceramic-using groups, which may have worked as catalysts for spreading ceramic style transitions throughout the region," said co-first author Daniel Fernandes.

Population size

Thanks in part to the large number of DNA samples available, the researchers were able to estimate ancient Caribbean population sizes before the arrival of Europeans. To the researchers' surprise, the numbers suggested that somewhere between 10,000 and 50,000 people were living in the combined region of Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and Puerto Rico in the centuries before Europeans arrived. This number is much lower than previous estimates and historical accounts of hundreds of thousands to millions of people.

"We set an important precedent for the estimation of population sizes with ancient DNA and showed how genetics and archaeology can work together to investigate old questions," said Ron Pinhasi, a co-senior author and Associate Professor at the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology at the University of Vienna.

Lasting legacy

By estimating that between 4 and 14 percent of their ancestry derived from the ancient people analysed, the study confirms previous findings that present-day people of the Caribbean harbor ancestry from three main groups—precontact Indigenous people, immigrant Europeans and Africans who were transported to this region as part of the slave trade—in different proportions across islands. "First in the Pacific and now in the Caribbean, ancient DNA has revealed how prehistoric seafaring human societies explored and colonized new regions," said Pinhasi.

Publication in "Nature":

A genetic history of the pre-contact Caribbean, D. Reich et al., Nature, 2020.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-03053-2

Wissenschaftlicher Kontakt

Univ.-Prof. Ron Pinhasi, PhD

Department für Evolutionäre AnthropologieUniversität Wien

1030 - Wien, Djerassiplatz 1

+43-1-4277-547 21

+43-664-60277-547 21

ron.pinhasi@univie.ac.at

Rückfragehinweis

Pia Gärtner, MA

Pressebüro der Universität WienUniversität Wien

1010 - Wien, Universitätsring 1

+43-1-4277-17541

pia.gaertner@univie.ac.at

Downloads:

Art_2_Journeys_End_painted_190825_01.jpg

Dateigröße: 952,54 KB

IMG_3548_01.jpg

Dateigröße: 2,96 MB