Where do the gender differences in the human pelvis come from?

25. März 2021A comparison with chimpanzees provides surprising insights

The pelvis is the part of the human skeleton with the largest differences between females and males. The female birth canal is on average more spacious and exhibits shape features that enable birth of a large baby with a big brain. In forensics, these pelvic differences are used for sex identification of human skeletons. Thus far it was unclear when these pelvic differences first appeared in human evolution. Barbara Fischer from the University of Vienna and her coauthors have published a study in Nature Ecology & Evolution presenting new insights into the evolutionary origin of pelvic sex differences.

Fossil remains of the human pelvis are rare because the pelvic bones do not preserve very well. Therefore, it has remained unclear when human sex differences in the pelvis evolved: jointly with upright walking, or later, together with the large human brains. "We have discovered that the pattern of sex differences in the human pelvis is probably much older than previously thought", says evolutionary biologist Barbara Fischer.

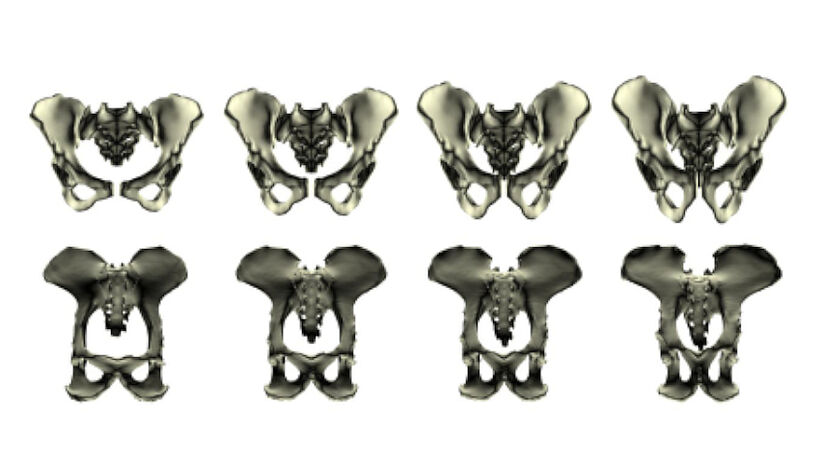

A team of biologists from the University of Vienna, the KLI for Evolution and Cognition Research, and the University of Calgary compared pelvic sex differences in humans with those in chimpanzees, the most closely-related living species to modern humans. Chimpanzees have much easier births than humans, because their fetuses are smaller. "We analyzed 3D data of pelves for these two species and found that they show the same pattern of sex differences, despite large overall species differences," says Fischer. Yet, the magnitude of the differences was only half as large in chimpanzees, compared to humans. The striking similarity of the pattern of pelvic sex differences in humans and chimpanzees strongly suggests that it was already present in the common ancestor of the two species. This implies that all the extinct hominin (human-like) species, including e.g., the Neandertals, probably had the same pattern.

Many mammals give birth to larger fetuses, relative to the birth canal of their mothers, compared to humans, e.g., bats and certain primates. These animals possess adaptations in their pelves to facilitate birth of large babies. At the same time, there are other mammals with tiny neonates, e.g., cats and opossums, which also have subtle sex differences in their pelves that resemble the human pattern. This suggests that these similarities in the pattern of pelvic sex differences reflect an old and evolutionarily conserved mammalian pattern. "We think that modern humans did not evolve this pattern de novo, but that we inherited it from earlier mammals that faced the same problem, namely having to give birth to relatively large fetuses," says Fischer. When our brains became increasingly large over the course of human evolution, the magnitude of pelvic sex differences was therefore able to increase rather rapidly, as the pelvic pattern and the underlying genetic and developmental machinery were already in place and did not have to evolve anew.

Publication in Nature Ecology & Evolution:

Barbara Fischer, Nicole D.S. Grunstra, Eva Zaffarini, Philipp Mitteroecker (2021)

Sex differences in the pelvis did not evolve de novo in modern humans. Nature Ecology and Evolution, in print.

DOI: 10.1038/s41559-021-01425-z

https://rdcu.be/chtQr

Wissenschaftlicher Kontakt

Dr. Barbara Fischer

Department für EvolutionsbiologieUniversität Wien

1030 - Wien, Djerassiplatz 1

+43-650-9904904

b.fischer@univie.ac.at

Rückfragehinweis

Pia Gärtner, MA

Pressebüro der Universität WienUniversität Wien

1010 - Wien, Universitätsring 1

+43-1-4277-17541

pia.gaertner@univie.ac.at

Downloads:

humanpelvisskull_01.tiff

Dateigröße: 2,32 MB

webt_01.jpg

Dateigröße: 144,38 KB